The ancient practice of English commoning tackles 21st century challenges

Ancient practice of commoning solving 21st century problems

Nature recovery, flood management, and carbon sequestration are getting a boost thanks to people coming together to keep alive centuries-old farming practices on common land [1].

It’s the focus of a three-year, £3m initiative, which ends next summer (2024), and is supported by 25 organisations across England [2].

The ‘Our Common Cause: Our Upland Commons’ project has brought commoners, landowners, and communities together on upland commons in Dartmoor, the Lake District, the Yorkshire Dales, and the Shropshire Hills [3].

Midway through, the results of the National Lottery Heritage Fund-supported project, have seen action taken to restore mires and ancient waterways, investigate old monuments, survey important butterflies, birds, and trees and tackle invasive plants. And 40 online ‘commons stories’, have been seen by over 20,000 people. [4]

Plus the economic viability of farming some of England’s most iconic land is also being addressed explains Julia Aglionby from the lead organisation, the Foundation for Common Land.

“Farming commoners are getting help to access new government funding schemes through a series of ‘ELM Readiness’ events. They need to be properly rewarded to manage these places to deliver a wide range of benefits for us all,” she adds.

Kate Ashbrook, from the Open Spaces Society, says another important aspect of the project is encouraging people to better understand and enjoy common land. “We have a right of access on foot to all commons, and a right on horseback to many,” she says.

Kate adds: “only 8% of England’s land is open access land, and 40% of that is on common land. The practice of commoning, with people exercising rights over land that is privately owned, dates back to the 13th century. Today common land accounts for just 3% of England and includes large tracts of our most well-loved, free to visit and ecologically rich landscapes. They are so important for our health and wellbeing.”

One key project partner is a landowner, the National Trust. Mike Innerdale, Director for the North of England, says: “the project is putting commoners, landowners and communities centre stage in delivering key public goods from these amazing places. It’s the sort of collaboration and knowledge sharing that is vital to tackling the many challenges our uplands and broader society faces today and over the next few years.”

For Julia Aglionby, the Our Uplands Commons project is a real success story amidst a rather bleak one for society, the environment and farming. Adding: “this project comes at a pivotal time for the 12 commons getting help - totalling 18,000 hectares. There are serious threats to commons and the system of commoning [4]. If not addressed we’ll lose these rare landscapes and the benefits they bring now and, in the future.”

The project is made possible thanks to grants from The National Lottery Heritage Fund, the Esmée Fairbairn and Garfield Weston Foundations. Plus input from local funders.

In the last 18 months project success stories include:

Lake District – famers are helping to develop a commons-proofed farm carbon calculator to record, manage and reduce their carbon footprint. A remote-control bracken cutter is helping commoners manage bracken on sensitive sites for nature and access. A butterfly survey discovered rare Small Pearl-bordered Fritillaries and landowners and commoners are being helped to protect them. And volunteers, led by archaeologists, investigated England’s highest Roman road, High Street, to understand it’s construction and age better.

An expert volunteer dig, deepening understanding of England’s highest Roman road, High Street, on common land in the Lake District. Credit: LDNPA

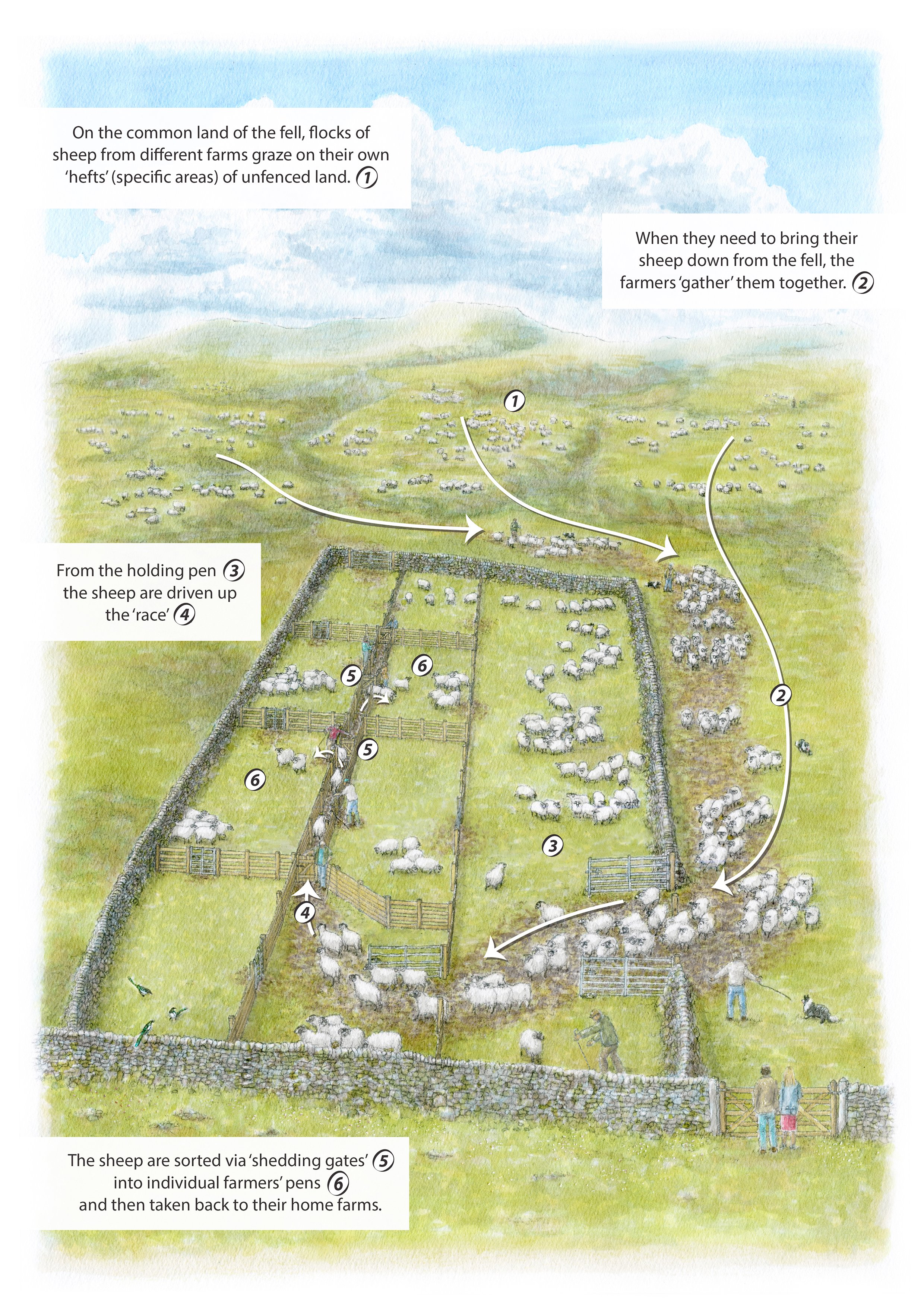

Yorkshire Dales - commoners on Ingleborough have learnt to monitor the rare and fragile habitats under their care, identifying key environmental indicator species as part of a farmer led habitat assessment programme. Sheep pens, an essential feature in the commoning landscape, have been reinstated and renovated to help with gathers. Accompanying illustrations explain the complex process of farmers working together to gather back their sheep at key points in the year. School children have explored and conserved Grassington common as part of residential outward-bound events. 800 visitors enjoyed watching shearing one weekend to better understand the links between farming and a landscape.

New sheep pens have replaced old, to help continue the tradition of commoning and gathering the sheep off the fells. Credit: Rob Fraser

Shropshire Hills – underway are initiatives to protect scheduled ancient monuments and improve bracken management for birds, butterflies and commoning systems. A shepherding trial, sees a shepherd moving stock to encourage grazing of less visited areas as a habitat management measure. Purchase of a mobile handling system, water bowser, quad bike, weed wiper and sprayer, is helping commoners in their practice of commoning. In one area the whole community is involved in developing a habitat management plan. Over 75 whinchat nests have been found and monitoring their broods, with cameras and heat sensors, is helping to reverse their decline. Visitors can take themselves on self-guided walks, using their phones, accompanied by a description of the common’s unique features. Youngsters are learning about commons through The John Muir Award programme.

Izzy Bell, an agricultural student who helps on John Heighway’s farm. Credit: Rob Fraser

Dartmoor – commoners associations are working with a mineral specialist to improve the health of the herds and flocks. A community task force of farmers, artists, specialists, and land owners restored two important spring mires. Farmers are sharing their farm business data with Duchy Rural Business School to understand true costs and benefits. Work by volunteers is repairing traditional boundaries, and increasing knowledge of trees and the fifth-longest stone row in the world. Pearl Bordered Fritillary numbers are increasing, with commoners controlling bracken and scrub, and bracken clearing is protecting stone hut circles. An ancient waterway, supplying water to farms, has been restored, thanks to commoners taking action. Hundreds of people learned about commoning, through gathers, events, and John Muir Awards.

Group that took part in a 2-day hedge laying course with Jeremy Weiss (he is wearing red in the centre of the pic) Credit: Rob Fraser

Image credits: Rob Fraser, Claire Hodgson, Our Upland Commons and illustration by Beth Cook

Footnotes

[1] First enshrined in law in the Magna Carta in 1215, common land traditionally sustained the poorest people in rural communities providing them with a source of wood, bracken for bedding and pasture for livestock. At one time nearly half of the land in Britain was common land, but from the C16th onwards the gentry excluded commoners from land which could be ‘improved’ through agriculture. Most common land is now found in areas with low agricultural potential, but with high conservation significance and natural beauty.

What are commons? Commons are privately owned spaces, over which others, the commoners, have rights, for example, to graze animals. Their owners include organisations like the National Trust, National Parks, utility companies, and private estates. Often, they look untouched and free from intervention but they are shaped by the action of commoners over centuries. Almost all common land is open access, which means we all have the right to enjoy recreation on foot on commons.

Who are the commoners? There are over 3,900 farmers who are commoners in England with the right to graze a common or use its resources, such as firewood, peat or bracken. Each flock on the commons has an area of land where they stay without fencing, this is known as a ‘heaf’, ‘heft’ or ‘lear’. This way of shared land management is called commoning and has protected some of the UK’s most spectacular landscapes for a thousand years.

Why do commons matter? These productive landscapes help us grow food, absorb rainfall, clean water, nurture wildlife, and take pleasure from recreation. The management of common land, when at sustainable levels, has ensured the survival of ancient monuments and rare wildlife, plants, birds and butterflies. Careful grazing can maintain the balance of delicate upland ecosystems on huge stretches of open landscape.

[2] The 25 partnership members are: Cumbria Wildlife Trust, Dartmoor Commoners’ Council, Dartmoor National Park Authority, Devon Wildlife Trust, Duchy of Cornwall, Dartmoor Preservation Association, Federation of Cumbria Commoners, Foundation for Common Land, Friends of the Lake District, Heather Trust, Lake District National Park Authority, Moorland Association, National Farmers’ Union, National Sheep Association, National Trust, Natural England, Open Spaces Society, RSPB, Shropshire Hills AONB Partnership, Shropshire Wildlife Trust, South West Water, Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority, Yorkshire Dales Millennium Trust, Yorkshire Wildlife Trust, University of Cumbria.

[3] The 12 commons involved in the project are: Dartmoor - Harford & Ugborough, Holne, Walkhampton. Lake District – Bampton, Derwent, Kinniside. The Shropshire Hills - Longmynd, Stiperstones, Clee Liberty. Yorkshire Dales - Brant Fell, Grassington Moor, Ingleborough.

[4] Commons Stories is a collection of articles, videos, audios and photographs from upland commons across England. They have been put together by writer Harriet Fraser and photographer Rob Fraser, with contributions from commoners and other experts. They reflect commoning practices and some of the challenges of building sustainable futures for people, nature and landscape in these special places. Find them here foundationforcommonland.org.uk/commons-stories

About The National Lottery Heritage Fund - Using money raised by the National Lottery, we inspire, lead and resource the UK’s heritage to create positive and lasting change for people and communities, now and in the future.

Since The National Lottery began in 1994, National Lottery players have raised over £43 billion for projects and more than 635,000 grants have been awarded across the UK. More than £30 million raised each week goes to good causes across the UK.